Chesterton and the Family

I have often said that G. K. Chesterton is perhaps my favourite Christian author. For those who may know nothing about him, I suggest you become acquainted with him, otherwise you really are missing out big time. See here for an overview of his life and work: https://billmuehlenberg.com/2011/01/24/notable-christians-g-k-chesterton/

He wrote on all manner of subjects, from theology to current events to arts and literature. He penned various works of fiction, including his famous Father Brown detection series, but also wrote plenty of apologetic works, defending the faith against the madness of modernity.

One topic that is found throughout his very broad corpus is that of marriage and family. In reaction to the moral and mental meltdowns of modern life, Chesterton mounted a sterling defence of the traditional family, taking on all the current attackers of it, whether the humanists, the feminists, the eugenicists, or the easy divorce crowd.

And his words are now classics on this. Who can forget what he said about the early feminists? Writing of the first feminist movement he quipped, “Twenty million young women rose to their feet with the cry ‘We will not be dictated to’ and proceeded to become stenographers.”

Plenty of other aphorisms and one-liners could be offered here. Just a few of the many would include:

“This triangle of truisms, of father, mother and child, cannot be destroyed; it can only destroy those civilisations which disregard it.”

“The family is the test of freedom; because the family is the only thing that the free man makes for himself and by himself.”

“The most extraordinary thing in the world is an ordinary man and an ordinary woman and their ordinary children.”

While his comments on the family are scattered all over the place – in his prose, his poetry, and his newspaper columns – one place where a terrific short piece on this is found is in his 1905 work, Heretics. In it is a chapter, “On Certain Modern Writers and the Institution of the Family.” It is loaded with typical Chestertonian wit and wisdom.

I would love to reprint it all here, but let me offer just two pages from this essay. Plenty of tremendous quotable quotes can be produced from this short section:

The institution of the family is to be commended for precisely the same reasons that the institution of the nation, or the institution of the city, are in this matter to be commended. It is a good thing for a man to live in a family for the same reason that it is a good thing for a man to be besieged in a city. It is a good thing for a man to live in a family in the same sense that it is a beautiful and delightful thing for a man to be snowed up in a street. They all force him to realise that life is not a thing from outside, but a thing from inside. Above all, they all insist upon the fact that life, if it be a truly stimulating and fascinating life, is a thing which, of its nature, exists in spite of ourselves. The modern writers who have suggested, in a more or less open manner, that the family is a bad institution, have generally confined themselves to suggesting, with much sharpness, bitterness, or pathos, that perhaps the family is not always very congenial. Of course the family is a good institution because it is uncongenial. It is wholesome precisely because it contains so many divergencies and varieties. It is, as the sentimentalists say, like a little kingdom, and, like most other little kingdoms, is generally in a state of something resembling anarchy. It is exactly because our brother George is not interested in our religious difficulties, but is interested in the Trocadero Restaurant, that the family has some of the bracing qualities of the commonwealth. It is precisely because our uncle Henry does not approve of the theatrical ambitions of our sister Sarah that the family is like humanity. The men and women who, for good reasons and bad, revolt against the family, are, for good reasons and bad, simply revolting against mankind. Aunt Elizabeth is unreasonable, like mankind. Papa is excitable, like mankind. Our youngest brother is mischievous, like mankind. Grandpapa is stupid, like the world; he is old, like the world.

Those who wish, rightly or wrongly, to step out of all this, do definitely wish to step into a narrower world. They are dismayed and terrified by the largeness and variety of the family. Sarah wishes to find a world wholly consisting of private theatricals; George wishes to think the Trocadero a cosmos. I do not say, for a moment, that the flight to this narrower life may not be the right thing for the individual, any more than I say the same thing about flight into a monastery. But I do say that anything is bad and artificial which tends to make these people succumb to the strange delusion that they are stepping into a world which is actually larger and more varied than their own. The best way that a man could test his readiness to encounter the common variety of mankind would be to climb down a chimney into any house at random, and get on as well as possible with the people inside. And that is essentially what each one of us did on the day that he was born.

This is, indeed, the sublime and special romance of the family. It is romantic because it is a toss-up. It is romantic because it is everything that its enemies call it. It is romantic because it is arbitrary. It is romantic because it is there. So long as you have groups of men chosen rationally, you have some special or sectarian atmosphere. It is when you have groups of men chosen irrationally that you have men. The element of adventure begins to exist; for an adventure is, by its nature, a thing that comes to us. It is a thing that chooses us, not a thing that we choose.

Falling in love has been often regarded as the supreme adventure, the supreme romantic accident. In so much as there is in it something outside ourselves, something of a sort of merry fatalism, this is very true. Love does take us and transfigure and torture us. It does break our hearts with an unbearable beauty, like the unbearable beauty of music. But in so far as we have certainly something to do with the matter; in so far as we are in some sense prepared to fall in love and in some sense jump into it; in so far as we do to some extent choose and to some extent even judge — in all this falling in love is not truly romantic, is not truly adventurous at all. In this degree the supreme adventure is not falling in love. The supreme adventure is being born. There we do walk suddenly into a splendid and startling trap. There we do see something of which we have not dreamed before. Our father and mother do lie in wait for us and leap out on us, like brigands from a bush. Our uncle is a surprise. Our aunt is, in the beautiful common expression, a bolt from the blue. When we step into the family, by the act of being born, we do step into a world which is incalculable, into a world which has its own strange laws, into a world which could do without us, into a world that we have not made. In other words, when we step into the family we step into a fairy-tale.

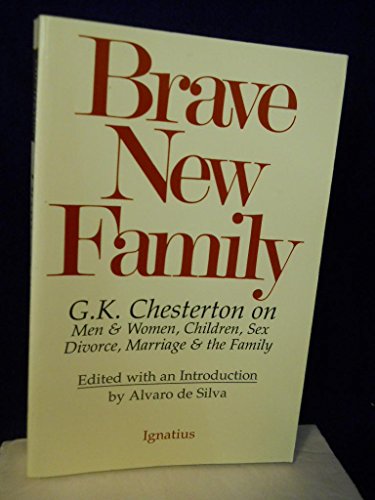

For more on Chesterton and the family, his short 1920 book The Superstition of Divorce: Collected Essays on Marriage and Divorce is also a tremendous resource. And for those without easy access to Chesterton’s works (although the Internet can be of real help here), Ignatius Press did us a great favour in 1990 by publishing Brave New Family: G. K. Chesterton on Men & Women, Children, Sex, Divorce, Marriage & the Family, edited by Alvaro de Silva.

So there are plenty of places to go to read up on marriage and the family from one of our greatest writers and Christian apologists of the past century. Happy reading.

[1389 words]

Thanks for the essay. I like him too, a wise and shrewd critic of modernity.

What incredible timing this article is for me, Bill! It must be a God “spark”! I am currently estranged from the majority of my family and have thought myself well out of the drama and conflicts that characterized it. Now, I’m not so sure, And that is a good thing. Chesterton’s perspective has reminded me of Donne’s “No man is an island” and given me much food for thought in terms of reconciling. God bless you, friend!

That is amazing, for what we take so much for granted, especially if we have had loving families is really quite a gamble and sadly so many children who need the same kind of love, being made an integral and irreplaceable part of a family find themselves unwanted, neglected, having to fight fights for survival which adults often don’t have to and so on.

But I have also often thought how those who want “diversity” actually reduce the variety God in His wisdom wants to provide for each family by insisting on more “sameness” than is good for life to prosper. Sameness is death says the second law of thermodynamics and that doesn’t only apply to material things.

Many blessings

Ursula Bennett

How anyone can rate this appalling anti-Semite is quite beyond me.

Thanks David. How anyone can push this appalling anti-Chesterton bigotry is quite beyond me.

http://www.chesterton.org/was-chesterton-antisemitic/

http://www.chesterton.org/shop/gilbert-vol-12/

Going through my wife’s Christian journals, she mentions “a poem of G. K. Chesterton’s about families.” Can anyone help me find this? It would be very meaningful to the cousin who is in the same journal entry. My wife passed away three years ago and I found her journal in a drawer.

Thanks Richard. He of course wrote several hundred poems, and likely a number of them were on the family. I pulled out my copy of his 1911 The Collected Poems of G. K. Chesterton and it is nearly 400 pages long. But one possible candidate would be “The Nativity” which you can read here:

https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/nativity-10

Or perhaps “The House of Christmas”:

https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-house-of-christmas-2/